Relative humidity

Relative humidity is a term used to describe the amount of water vapor that exists in a gaseous mixture of air and water vapor.

Contents |

Definition

The relative humidity  of an air-water mixture is defined as the ratio of the partial pressure of water vapor

of an air-water mixture is defined as the ratio of the partial pressure of water vapor  in the mixture to the saturated vapor pressure of water

in the mixture to the saturated vapor pressure of water  at a prescribed temperature.

at a prescribed temperature.

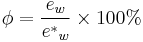

Relative humidity is normally expressed as a percentage and is calculated by using the following equation:[1]

Measurement

The relative humidity of an air-water vapor mixture can be determined through the use of psychrometric charts if both the dry bulb temperature (T) and the wet bulb temperature (Tw) of the mixture are known. These quantities are readily estimated by using a sling psychrometer.

There are several empirical correlations that can be used to estimate the saturated vapor pressure of water vapor as a function of temperature. The Antoine equation is among the least complex of these formulas, having only three parameters (A, B, and C). Other correlations, such as the those presented by Goff-Gratch and Magnus Tenten, are more complicated but yield better accuracy. The correlation presented by Buck [2] is commonly encountered in the literature and provides a reasonable balance between complexity and accuracy:

where  is the dry bulb temperature expressed in degrees Celsius (°C),

is the dry bulb temperature expressed in degrees Celsius (°C),  is the absolute pressure expressed in millibar (mbar), and

is the absolute pressure expressed in millibar (mbar), and  is the saturated vapor pressure expressed in hectopascals (hPa).

is the saturated vapor pressure expressed in hectopascals (hPa).

Buck has reported that the maximum relative error is less than 0.20% between -20°C and +50°C when the this particular form of the generalized formula is used to estimate the saturated vapor pressure of water.

A common misconception

Often the notion of air holding water vapor is presented to describe the concept of relative humidity. This, however, is a misconception. Air is a mixture of gases (nitrogen, oxygen, argon, water vapor, and other gases) and as such the constituents of the mixture simply act as a transporter of water vapor but are not a holder of it.

Humidity is wholly understood in terms of the physical properties of water and thus is unrelated to the concept of air holding water.[3][4] In fact, an air-less volume can contain water vapor and therefore the humidity of this volume can be readily determined.

The misconception that air holds water is likely the result of the use of the word saturation, which is often misused in descriptions of relative humidity. In the present context the word saturation refers to the state of water vapor,[5] not the solubility of one material in another.

Significance of relative humidity

Climate control

Climate control refers to the control of temperature and relative humidity for human comfort, health and safety, and for the technical requirements of machines and processes, in buildings, vehicles and other enclosed spaces.

Comfort

Humans are sensitive to humid air because the human body uses evaporative cooling as the primary mechanism to regulate temperature. Under humid conditions, the rate at which perspiration evaporates on the skin is lower than it would be under arid conditions. Because humans perceive the rate of heat transfer from the body rather than temperature itself [6], we feel warmer when the relative humidity is high than when it is low.

For example, if the air temperature is 24 °C (75 °F) and the relative humidity is zero percent, then the air temperature feels like 21 °C (69 °F).[7] If the relative humidity is 100 percent at the same air temperature, then it feels like 27 °C (80 °F).[7] In other words, if the air is 24 °C and contains saturated water vapor, then the human body cools itself at the same rate as it would if it were 27 °C and dry.[7] The heat index and the humidex are indices that reflect the combined effect of temperature and humidity on the cooling effect of the atmosphere on the human body.

Buildings

When controlling the climate in buildings using HVAC systems the key is to control the relative humidity in a comfortable range - low enough to be comfortable but high enough to avoid problems associated with very dry air.

When the temperature is high and the relative humidity is low, evaporation of water is rapid; soil dries, wet clothes hung on a line or rack dry quickly, and perspiration readily evaporates from the skin. Wooden furniture can shrink causing the paint that covers these surfaces to fracture.

When the temperature is high and the relative humidity is high, evaporation of water is slow. When relative humidity approaches 100 percent, condensation can occur on surfaces, leading to problems with mold, corrosion, decay, and other moisture-related deterioration.

Certain production and technical processes and treatments in factories, laboratories, hospitals and other facilities require specific relative humidity levels to be maintained using humidifiers, dehumidifiers and associated control systems.

Vehicles

The same basic principles as in buildings, above, apply. In addition there may be safety considerations. For instance high humidity inside a vehicle can lead to problems of condensation, such as misting of windshields and shorting of electrical components.

In sealed vehicles and pressure vessels such as pressurised airliners, submersibles and spacecraft these considerations may be critical to safety, and complex environmental control systems including equipment to maintain pressure are needed. For example, airliner fuselages are susceptible to corrosion from humidity, and avionics are susceptible to condensation, and as the failure of either is potentially catastrophic, airliners operate with low internal relative humidity, often under 10%, especially on long flights. The low humidity is a consequence of drawing in the very cold air with a low absolute humidity, which is found at airliner cruising altitudes. Subsequent warming of this air lowers its relative humidity. This causes discomfort such as sore eyes, dry skin, and drying out of mucosa, but humidifiers are not employed to raise it to comfortable mid-range levels because dry air is essential to safe flight.

Pressure dependence

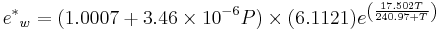

The relative humidity of an air-water system is dependent not only on the temperature but also on the absolute pressure of the system of interest. This dependence is demonstrated by considering the air-water system shown below. The system is closed (i.e. no matter enters or leaves the system).

If the system at State A is isobarically heated (heating with no change in system pressure) then the relative humidity of the system decreases because the saturated vapor pressure of water increases with increasing temperature. This is shown in State B.

If the system at State A is isothermally compressed (compressed with no change in system temperature) then the relative humidity of the system increases because the partial pressure of water in the system increases with increasing system pressure. This is shown in State C.

Therefore a change in relative humidity can be explained by a change in system temperature, a change in the absolute pressure of the system, or change in both of these system properties.

Enhancement factor

The enhancement factor  is defined as the ratio of the saturated vapor pressure of water in moist air

is defined as the ratio of the saturated vapor pressure of water in moist air  to the saturated vapor pressure of pure water vapor.

to the saturated vapor pressure of pure water vapor.

The enhancement factor is equal to unity for ideal gas systems. However, in real systems the interaction effects between gas molecules result in a small increase of the saturation vapor pressure of water in air relative to saturated vapor pressure of pure water vapor. Therefore, the enhancement factor is normally slightly greater than unity for real systems.

The enhancement factor is commonly used to correct the saturated vapor pressure of water vapor when empirical relationships, such as those developed by Wexler, Goff, and Gratch, are used to estimated the properties of psychrometric systems.

Buck has reported that, at sea level, the vapor pressure of water in saturated moist air amounts to an increase of approximately 0.5% over the saturated vapor pressure of pure water.[8]

Related concepts

The term relative humidity is reserved for systems of water vapor in air. The term relative saturation is used to describe the analogous property for systems consisting of a condensable phase other than water in a non-condensable phase other than air.[9]

Other important facts

A gas in this context is referred to as saturated when the vapor pressure of water in the air is at the equilibrium vapor pressure for water vapor at the temperature of the gas and water vapor mixture; liquid water (and ice, at the appropriate temperature) will fail to lose mass through evaporation when exposed to saturated air. It may also correspond to the possibility of dew or fog forming, within a space that lacks temperature differences among its portions, for instance in response to decreasing temperature. Fog consists of very minute droplets of liquid, primarily held aloft by isostatic motion (in other words, the droplets fall through the air at terminal velocity, but as they are very small, this terminal velocity is very small too, so it doesn't look to us like they are falling and they seem to be being held aloft).

The statement that relative humidity (RH%) can never be above 100%, while a fairly good guide, is not absolutely accurate, without a more sophisticated definition of humidity than the one given here. An arguable exception is the Wilson cloud chamber which uses, in nuclear physics experiments, an extremely brief state of "supersaturation" to accomplish its function.

For a given dewpoint and its corresponding absolute humidity, the relative humidity will change inversely, albeit nonlinearly, with the temperature. This is because the partial pressure of water increases with temperature – the operative principle behind everything from hair dryers to dehumidifiers.

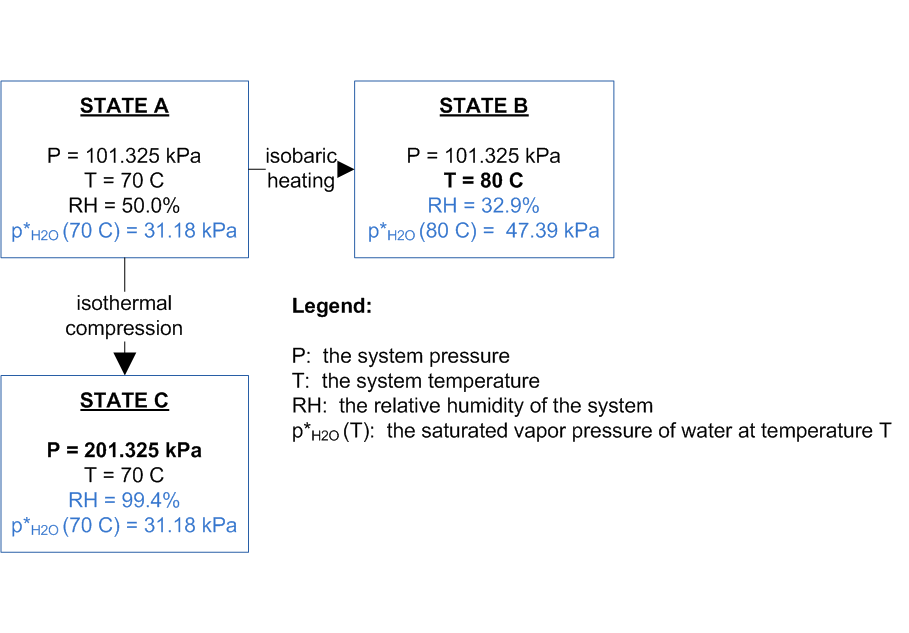

Due to the increasing potential for a higher water vapor partial pressure at higher air temperatures, the water content of air at sea level can get as high as 3% by mass at 30 °C (86 °F) compared to no more than about 0.5% by mass at 0 °C (32 °F). This explains the low levels (in the absence of measures to add moisture) of humidity in heated structures during winter, indicated by dry skin, itchy eyes, and persistence of static electric charges. Even with saturation (100% relative humidity) outdoors, heating of infiltrated outside air that comes indoors raises its moisture capacity, which lowers relative humidity and increases evaporation rates from moist surfaces indoors (including human bodies.)

Similarly, during summer in humid climates a great deal of liquid water condenses from air cooled in air conditioners. Warmer air is cooled below its dewpoint and the excess water vapor condenses. This phenomenon is the same as that which causes water droplets to form on the outside of a cup containing an ice-cold drink.

A useful rule of thumb is that the maximum absolute humidity doubles for every 20 °F or 10 °C increase in temperature. Thus, the relative humidity will drop by a factor of 2 for each 20 °F or 10 °C increase in temperature, assuming conservation of absolute moisture. For example, in the range of normal temperatures, air at 70 °F or 20 °C and 50% relative humidity will become saturated if cooled to 50°F or 10 °C, its dewpoint and 40 °F or 5 °C air at 80% relative humidity warmed to 70 °F or 20 °C will have a relative humidity of only 29% and feel dry. By comparison, a relative humidity between 40% and 60% is considered healthy and comfortable in comfort controlled environments (ASHRAE Standard 55 - see thermal comfort).

Water vapor is a lighter gas than air at the same temperature, so humid air will tend to rise by natural convection. This is a mechanism behind thunderstorms and other weather phenomena. Relative humidity is often mentioned in weather forecasts and reports, as it is an indicator of the likelihood of precipitation, dew, or fog. In hot summer weather, it also increases the apparent temperature to humans (and other animals) by hindering the evaporation of perspiration from the skin as the relative humidity rises. This effect is calculated as the heat index or humidex.

A device used to measure humidity is called a hygrometer, one used to regulate it is called a humidistat, or sometimes hygrostat. (These are analogous to a thermometer and thermostat for temperature, respectively.)

See also

- Humidity

- Concentration

- Heat index

- Dew point

- Dew point depression

- Humidity indicator

- Humidity indicator card

- Hygrometer

- Hygrometer

- Thermo Hygrometer

- Digital Hygrometer

- Psychrometrics

- Saturation vapor density

References

- ↑ Perry, R.H. and Green, D.W, Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (7th Edition), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-049841-5 , Eqn 12-7

- ↑ http://www.google.ca/#hl=en&safe=off&&sa=X&ei=T7xqTN-UFYy4sQPFy-XGDw&ved=0CBQQvwUoAQ&q=new+equations+for+computing&spell=1&fp=61ed78eac09af644

- ↑ http://www.atmos.umd.edu/~stevenb/vapor/

- ↑ http://www.ems.psu.edu/~fraser/Bad/BadFAQ/BadCloudsFAQ.html

- ↑ http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/hframe.html

- ↑ http://curious.astro.cornell.edu/question.php?number=86

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 What is relative humidity and how does it affect how I feel outside?

- ↑ Arden L. Buck, New Equations for Computing Vapor Pressure and Enhancement Factor, Journal of Applied Meterology, December 1981, Volume 20, Page 1529.

- ↑ http://blowers.chee.arizona.edu/201project/GLsys.interrelatn.pg1.HTML

- Himmelblau, David M. (1985454545). Basic Principles And Calculations In Chemical Engineering. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-066572-X.

- Perry, R.H. and Green, D.W (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (7th Edition). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049841-5.

External links

- Glossary definition of psychrometric tables - National Snow and Ice Data Center

- Bad Clouds FAQ, PSU.edu

- Simulation of the indoors/outdoors change relationship